Not long ago, the defeat of cancer

seemed inevitable. Decades of research would soon pay off with a

completely fresh approach, an arsenal of clever new drugs to attack

the very forces that make tumors grow and spread and kill.

No more chemotherapy, the

thinking went. No more horrid side effects. Just brilliantly

designed drugs that stop cancer while leaving everything

else untouched.

Those elegant drugs

are now here. But so is cancer.

The approach, which

appeared so straightforward, has proven disappointingly

difficult to turn into broadly useful treatments.

Some now wonder if malignancy will ever be reliably

and predictably cured.

The dearth of

substantial impact so far suggests the fight against

cancer will continue to be a tedious slog, and

victories will be scored in weeks or months of extra

life, not years. The full potential of the new

approach may take decades to be realized.

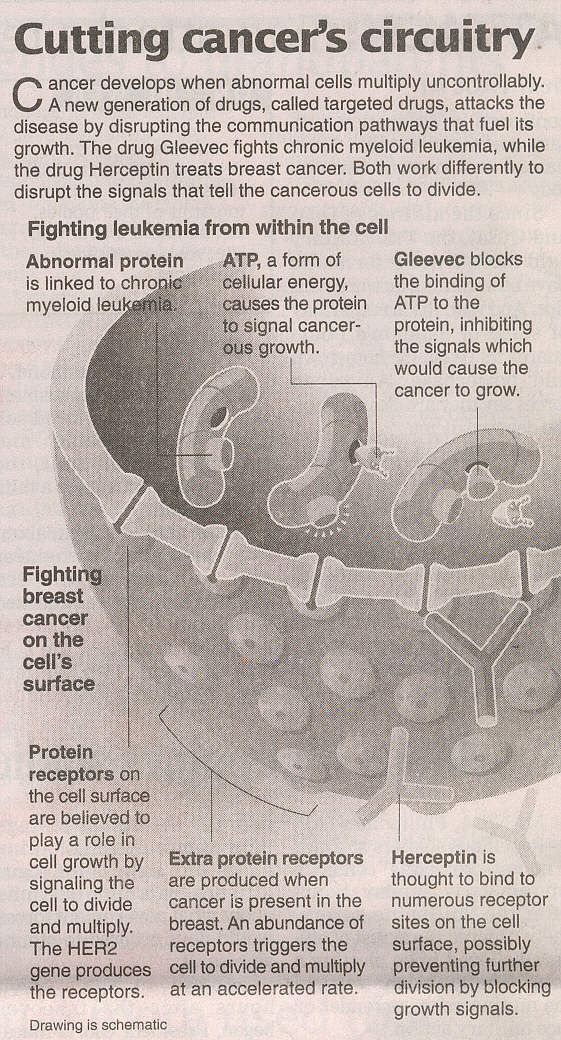

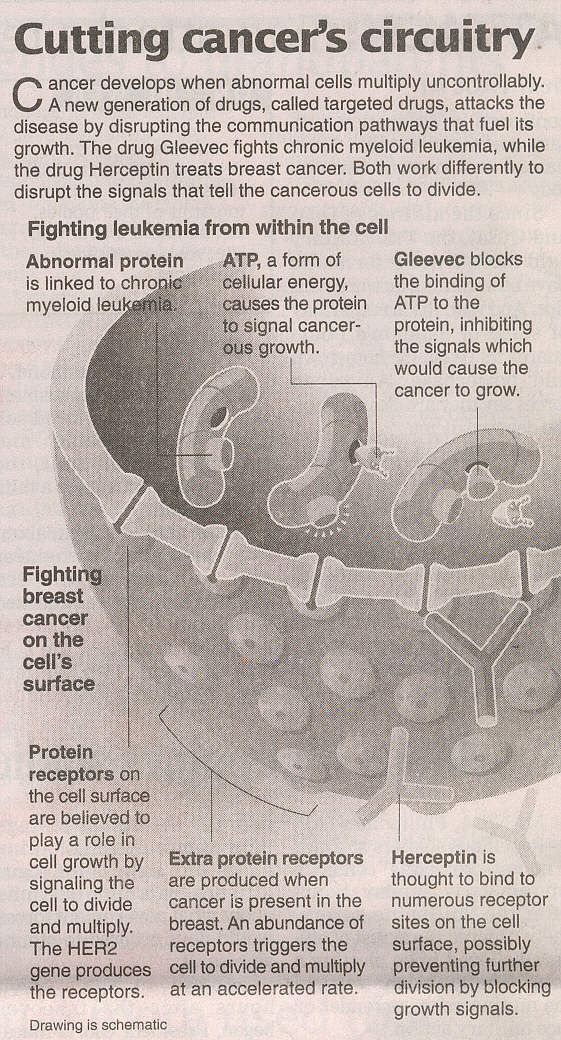

The drugs,

called targeted therapies, are intended to arrest cancer

by disrupting the internal signals that fuel its

unruly growth. Unlike chemo, which attacks all

dividing cells, these medicines are crafted with pinpoint

accuracy to go after the genetically controlled

irregularities that make cancer unique.

Several have made it through

testing, but despite their apparent bull's-eye hits, lasting

results are rare. Instead, these new drugs turn out to

be about as effective -- or as powerful -- as old-line

chemotherapy. Aimed at the major forms of cancer, they

work spectacularly for a lucky few and modestly for

some.

But for most? Not at all.

Doctors have many theories

about what's gone wrong. But it is clear that cancer is

a surprisingly robust foe, packed with convoluted

backup systems that kick in when threatened by the

new drugs.

At best,

experts now expect knocking down cancer will require an elaborate

mixture of targeted drugs, assembled to match the distinct

biology of each person's cancer.

"It's a much more

complicated problem than anyone ever appreciated," says

Dr. Leonard Saltz, a colon cancer expert at Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. "It will, unfortunately,

be with us for a long time."

The job is so

daunting, especially for advanced cancers propelled by

potentially dozens of nefarious genetic mutations,

that scientists are even rethinking the goal of cancer

research.

"Society as a whole, and

most of the medical professional, have it wrong, understanding

we'll make up one morning and find out cancer is cured.

It won't happen. The public should give it up,"

says Dr. Craig Henderson, a breast cancer specialist

at the University of California, San Francisco,

and president of Access Oncology, a drug developer.

"What we have

learned by these billions of dollars invested in

cancer biology is that cancer are us," he goes on.

True, cancer is different. But not different enough.

"Identify what makes cancer unique and wipe it out?

That won't happen. We cannot wipe out the cancer

without wiping out a lot of the rest of us."

Henderson and many others

have shifted their sights to something less -- converting

cancer into a chronic disease, like diabetes or AIDS.

Treatments might slow or even stop its worst effects

so people survive for years reasonably free

of symptoms.

Dr. Andrew

von Eschenbach, head of the National Cancer

Institute, argues that a cure is not even

necessary if this can be done, something he

optimistically hopes to see by 2015. But eliminate cancer?

"Not in the foreseeable future," he says.

Still, experts

concede there is no firm evidence that targeted

treatments will tame cancer to a chronic condition,

either. Certainly, the ones tested so far do not often

come close to this for the common varieties, such as

lung, breast, colon and prostate cancer.

Although targeted

therapies have their origins in basic cancer discoveries

of the 1980's, the story for many began at a meeting of

the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 1998.

Researchers were thrilled to hear of the first convincing

demonstration that a targeted drug could slow the course

of cancer even a little. It was proof that the principle

is sound.

Usually wary

oncologists rhapsodized about a new era of treatment.

"A tidal wave," one of them called it. Even then,

no one predicted quick cures. But they clearly felt

they at least had the key to getting inside cancer

and fixing it.

The drug that

caused the euphoria, Herceptin, became a standard

treatment for spreading breast cancer, typically

delaying progression by a few months in the quarter of

victims with a particular genetic profile.

Since Herceptin,

targeted drugs have become the prevailing approach

in cancer research. Whenever any of these make

slight progress, the news is widely and sometimes

breathlessly reported. An estimated two-thirds of

the nearly 400 cancer medicines in human study take

this tack. Yet researchers do not envision successes

any more spectacular from this pipeline than the

modest effects of the handful already on the market.

"Right now, in the

short run, we can bring an occasional miracle and have

an overall small benefit," says Dr. John Glaspy,

medical director of UCLA's surgical oncology center.

"But there has not been a major improvement on what

happens to them ultimately."

Furthermore, the dream of

abandoning chemotherapy has largely evaporated. Even the

targeted drugs' small benefits are typically seen only

when combined with standard chemo.

Cancer doctors facing

waiting rooms full of dying cancer patients, with little

to offer but easing misery and perhaps a few extra months

of survival, clearly had wishes for more.

"The hope was that these

targeted therapies would be the new magic bullet and

would cure cancer," says Dr. DAvid Decker, an oncologist

at William Beaumont Hospital outside Detroit. "It's fair

to say they haven't panned out the way we thought they

would."

The targeted drugs

have been most impressive against cancers of the blood

and immune system, which are easier to control than the

most common organ tumors. For instance, about half of

patients getting Rituxan for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma have

at least a 50 percent reduction in their cancer, and

the improvement lasts an average of a year before the

disease progresses again.

The one striking

success, Gleevec, unfortunately works only against two

rare blood and digestive cancers that involve unusually

simple signaling pathways, offering ideal targets.

Even so, Gleevec's stunning effects -- close to 90 percent

initially get better -- often wear off in time.

In 2001, Dean

Gordanier, a Boston tax attorney with a cancer-swollen

belly, was "pretty much dying" when he started on Gleevec.

For 18 months, it was a miracle. He gained weight and

went back to work. Then, the day before Christmas,

he learned the tumor was growing again.

For most who win

a cancer reprieve, that would be the end. But as it

turned out, another experimental targeted drug was

available at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and

Gordanier's cancer is in retreat again, although he

expects this medicine, too, will eventually fail.

"I feel like

I'm riding the crest of a wave," he says. "It could

dump me at any time, but right now I'm cruising."

Dr. Brian

Druker of Oregon Health and Sciences University, one of

Gleevec's developers, says, "What Gleevec tells us

is if we have the right target and the right drug,

we will have spectacular results. Until then, we will

be mired in incremental gains."

Those gains seem

especially incremental against the far more complicated

common cancers. For instance, the drug Iressa was approved

in May on evidence that it temporarily shrinks advanced

lung cancer in just 10 percent of patients. Doctors often

assume drugs will work better if given earlier in the

disease. But when Iressa was combined with chemotherapy

in newly diagnosed lung cancer, the patients did not

respond to it at all.

Others in the pipeline

seem hardly more potent.

At this June's

clinical oncology meeting, doctors reported the results

with two targeted drugs for advanced colon cancer:

A growth signal blocker called Erbitux (the same medicine

that ensnarled Martha Stewart in a Wall Street scandal)

temporarily shrank tumors in a quarter of patients.

And Avastin, intended to stop cancers from building

blood vessels, improved average survival by four months.

In theory, all of these

drugs should work better, because they block the communication

pathways hijacked by the genetic mutations that become

cancer.

Cancer occurs when five to 10

ordinary genes develop mutations in a single cell over a person's

lifetime, the consequence of biological insults like smoking or

just bad luck. As a result, the genes may get stuck in hyperdrive,

churning out huge amounts of growth stimulating proteins,

or perhaps they get turned off inappropriately, robbing

cells of their brakes. Whatever the problem, the result is

cells that divide over and over; that take root in parts

of the body where they don't belong; that lose the normal

instinct to self-destruct when their wiring goes awry;

and that they never die.

This mess is fueled

by hundreds, even thousands, of individual proteins.

The process of making new blood vessels alone may entail

30 or 40 of them lined up in several signaling pathways.

With targeted drugs,

scientists envisioned bringing the entire process to a halt

by chemically knocking out a single protein link in one

chain of communication. Like a cut phone line, no signal gets

through. Therefore, no more growth and no new cancer.

Although the process

has not worked out to be this simple, many in the field believe

that eventual progress is likely. Maybe the best-case

scenario is spun out bythe Dana Farber's Dr. William

Kaelin. He theorizes that a few key pathways will prove

important in many kinds of cancer, and drugs will be created

to effectively block them.

Several dozen drugs

may offer enough choices to cover all the typical genetic

combinations at work in cancer. "This is the belief that is

driving all of us," says Kaelin. With the right mix of three

or four drugs for any individual, "we will make a major

inroad into the common adult tumors, such as lung, colon

and breast cancer."